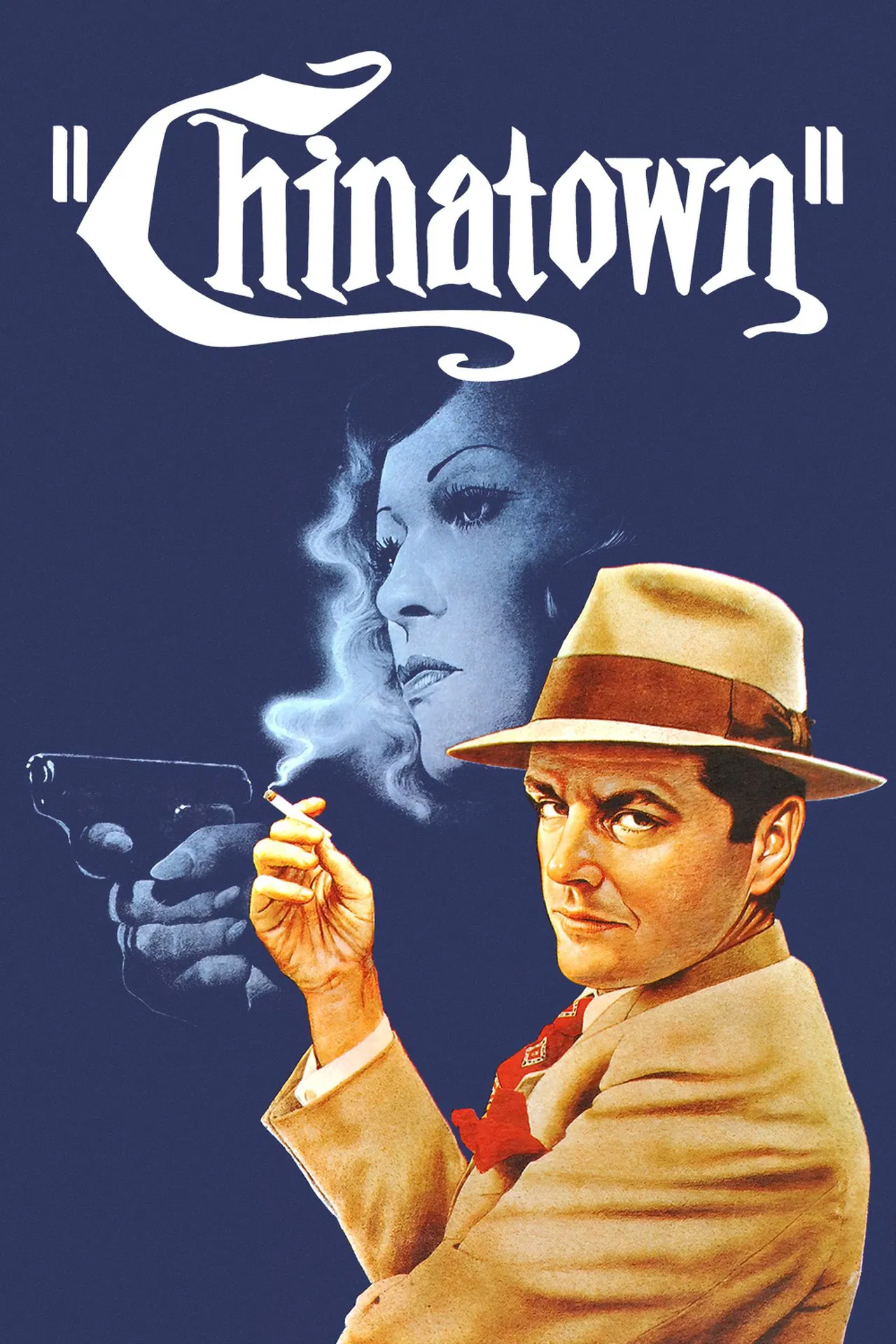

Chinatown

1974

Reviewed on: Jun 8, 2025

Review

For me, Chinatown was one of those films whose "classic" status made it an obligatory viewing for any self-respecting film enthusiast but one that didn't spark much excitement when it arrived at the top of my watchlist. Nevertheless, a recent relocation to California made the film have some personal relevance and was the final push in my decision to take it on. And while many other of the go-to "classics" have struck me as more important or even masterful, Chinatown was by no means devoid of intent and was quite successful in creating a tone of melancholy: everything feels like a bittersweet goodbye after nostalgic reflection.

To dissect how Chinatown sustains this feeling, we first look to the legacy of the noir genre. We all know the tropes–the morally ambiguous detective, the distraught "dame" who kicks off the mystery, the Scooby Doo red herrings, and off-handed narration (which, interestingly, was originally planned for Chinatown but didn't make the final cut). And while easy to dismiss entire genres as unoriginal by merely pointing out recurrences, the tropes existed for a reason. They emerged from the uncertainty and desperation of the 1940s, gave rise to compelling characters, and demanded close viewer attention. The result was some of the greatest, and yes trope-y, films of all time.

In embodying the most iconic commonalities of successful noirs, Chinatown pays homage. By 1974, noir had been somewhat played out in American cinema with this film sitting distinctly at the genre's twilight. So automatically, this sense of longing for times-gone-by underscores the film, achieved merely by the choice of genre. In Jake Gittes (Jack Nicholson), a classic anti-hero chasing truth without the promise of financial reward, we're reminded of Sam Spade and Rick Blaine, the brooding leads of 1940s noir. Even though few alive today remember the significance of these films upon their debut, Chinatown's setting and the implementation of universally-recognized film noir devices invites the audience to reach back in their memory to their parents' and grandparents' favorite films. The experience is deeply melancholic and nostalgic.

Yet as we examine a little closer, we see this tone present, not only in the genre and setting, but in the characters and their dialogue. Gittes constantly refers to his past experience as a PI motivating his choices throughout the film, and it's the uncovering of Cross family's ancient history that directs the major events of the mystery. This film, its characters, and the events it concerns all focus intensely on reflections of past times eliciting this feeling of sentimentality for events that no one in the audience was present for. Ultimately and especially, it's this sadness–this ache that the past is indeed passed–that makes the ending hit so hard. In the city of his early days (Chinatown), Jake Gittes eerily relives the events that once drove him away. What begins as a search for truth ends as a return to tragedy—and Gittes, with the audience, learns that no matter how far he strays, the past is never far behind.